Resistivity

Electrical resistivity (also known as specific electrical resistance or volume resistivity) is a measure of how strongly a material opposes the flow of electric current. A low resistivity indicates a material that readily allows the movement of electrical charge. The SI unit of electrical resistivity is the ohm metre [Ω m].

Contents |

Definitions

Electrical resistivity ρ (Greek: rho) is defined by,

where

- ρ is the static resistivity (measured in volt-metres per ampere, V m/A);

- E is the magnitude of the electric field (measured in volts per metre, V/m);

- J is the magnitude of the current density (measured in amperes per square metre, A/m²).

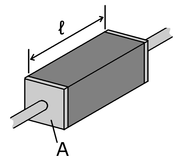

The electrical resistivity ρ can also be given by,

where

- ρ is the static resistivity (measured in ohm-metres, Ω m)

- R is the electrical resistance of a uniform specimen of the material (measured in ohms, Ω)

is the length of the piece of material (measured in metres, m)

is the length of the piece of material (measured in metres, m)- A is the cross-sectional area of the specimen (measured in square metres, m²).

Finally, electrical resistivity is also defined as the inverse of the conductivity σ (sigma), of the material, or

Explanation

The reason resistivity has the dimension units of ohm-metres can be seen by transposing the definition to make resistance the subject:

The resistance of a given sample will increase with the length, but decrease with greater cross sectional area. Resistance is measured in ohms. Length over area has units of 1/distance. To end up with ohms, resistivity must be in the units of "ohms × distance" (SI ohm-metre, US ohm-inch).

In a hydraulic analogy, increasing the diameter of a pipe reduces its resistance to flow, and increasing the length increases resistance to flow (and pressure drop for a given flow).

Table of resistivities

This table shows the resistivity and temperature coefficient of various materials at 20 °C (68 °F)

| Material | Resistivity [Ω·m] at 20 °C | Temperature coefficient* [K−1] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver | 1.59×10−8 | 0.0038 | [1][2] |

| Copper | 1.68×10−8 | 0.0039 | [2] |

| Gold | 2.44×10−8 | 0.0034 | [1] |

| Aluminium | 2.82×10−8 | 0.0039 | [1] |

| Calcium | 3.36x10−8 | 0.0041 | |

| Tungsten | 5.60×10−8 | 0.0045 | [1] |

| Zinc | 5.90×10−8 | 0.0037 | [3] |

| Nickel | 6.99×10−8 | 0.006 | |

| Iron | 1.0×10−7 | 0.005 | [1] |

| Platinum | 1.06×10−7 | 0.00392 | [1] |

| Tin | 1.09×10−7 | 0.0045 | |

| Lead | 2.2×10−7 | 0.0039 | [1] |

| Manganin | 4.82×10−7 | 0.000002 | [4] |

| Constantan | 4.9×10−7 | 0.000008 | [5] |

| Mercury | 9.8×10−7 | 0.0009 | [4] |

| Nichrome[6] | 1.10×10−6 | 0.0004 | [1] |

| Carbon (amorphous) | 5-8×10−4 | −0.0005 | [1][7] |

| Carbon (graphite)[8] | 2.5-5.0×10−6 ⊥ basal plane 3.0×10−3 // basal plane |

[9] | |

| Carbon (diamond)[10] | ~1012 | [11] | |

| Germanium[10] | 4.6×10−1 | −0.048 | [1][2] |

| seawater | 2×10−1 | ? | |

| Silicon[10] | 6.40×102 | −0.075 | [1] |

| Glass | 1010 to 1014 | ? | [1][2] |

| Hard rubber | approx. 1013 | ? | [1] |

| Sulfur | 1015 | ? | [1] |

| Paraffin | 1017 | ? | |

| Quartz (fused) | 7.5×1017 | ? | [1] |

| PET | 1020 | ? | |

| Teflon | 1022 to 1024 | ? |

*The numbers in this column increase or decrease the significand portion of the resistivity. For example, at 30 °C (303 K), the resistivity of silver is 1.65×10−8. This is calculated as Δρ = α ΔT ρo where ρo is the resistivity at 20 °C (in this case) and α is the temperature coefficient.

The effective temperature coefficient varies with temperature and purity level of the material. The 20 °C value is only an approximation when used at other temperatures. For example, the coefficient becomes lower at higher temperatures for copper, and the value 0.00427 is commonly specified at 0 °C. For further reading: http://library.bldrdoc.gov/docs/nbshb100.pdf.

Considering the two extreme examples in this table, why is Teflon such an excellent insulator and silver such an efficient conductor?

The chemical structure of Teflon (a synthetic polymer) is essentially a chain of carbon atoms, with each carbon bonded to two other carbons and two fluorine atoms. Fluorine (which virtually surrounds the relatively conductive carbon atoms) is the most electronegative of the elements; a neutral fluorine needs only one more electron to fill its valence shell. Thus, while fluorine readily accepts electrons, it does not give them back without a fight. This situation is not conducive to the free flow of electrons. See electron affinity and ionization energy (periodic) tables for more elucidation here—this all relates to reduction potentials and the nature of redox reactions as a whole, though the correlation is not always direct because reduction potential data give information about whole molecules, not atomic elements.

The extremely low resistivity (high conductivity) of silver is characteristic of metals. George Gamow tidily summed up the nature of the metals' dealings with electrons in his science-popularizing book, One, Two, Three...Infinity (1947): "The metallic substances differ from all other materials by the fact that the outer shells of their atoms are bound rather loosely, and often let one of their electrons go free. Thus the interior of a metal is filled up with a large number of unattached electrons that travel aimlessly around like a crowd of displaced persons. When a metal wire is subjected to electric force applied on its opposite ends, these free electrons rush in the direction of the force, thus forming what we call an electric current." More technically, the free electron model gives a basic description of electron flow in metals.

Temperature dependence

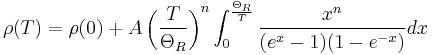

In general, electrical resistivity of metals increases with temperature, while the resistivity of semiconductors decreases with increasing temperature. In both cases, electron–phonon interactions can play a key role. At high temperatures, the resistance of a metal increases linearly with temperature. As the temperature of a metal is reduced, the temperature dependence of resistivity follows a power law function of temperature. Mathematically the temperature dependence of the resistivity ρ of a metal is given by the Bloch–Grüneisen formula:

where  is the residual resistivity due to defect scattering, A is a constant that depends on the velocity of electrons at the fermi surface, the Debye radius and the number density of electrons in the metal.

is the residual resistivity due to defect scattering, A is a constant that depends on the velocity of electrons at the fermi surface, the Debye radius and the number density of electrons in the metal.  is the Debye temperature as obtained from resistivity measurements and matches very closely with the values of Debye temperature obtained from specific heat measurements. n is an integer that depends upon the nature of interaction:

is the Debye temperature as obtained from resistivity measurements and matches very closely with the values of Debye temperature obtained from specific heat measurements. n is an integer that depends upon the nature of interaction:

- n=5 implies that the resistance is due to scattering of electrons by phonons (as it is for simple metals)

- n=3 implies that the resistance is due to s-d electron scattering (as is the case for transition metals)

- n=2 implies that the resistance is due to electron–electron interaction.

As the temperature of the metal is sufficiently reduced (so as to 'freeze' all the phonons), the resistivity usually reaches a constant value, known as the residual resistivity. This value depends not only on the type of metal, but on its purity and thermal history. The value of the residual resistivity of a metal is decided by its impurity concentration. Some materials lose all electrical resistivity at sufficiently low temperatures, due to an effect known as superconductivity.

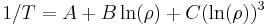

An even better approximation of the temperature dependence of the resistivity of a semiconductor is given by the Steinhart–Hart equation:

where A, B and C are the so-called Steinhart–Hart coefficients.

This equation is used to calibrate thermistors.

In non-crystalline semi-conductors, conduction can occur by charges quantum tunnelling from one localised site to another. This is known as variable range hopping and has the characteristic form of  , where n=2,3,4 depending on the dimensionality of the system.

, where n=2,3,4 depending on the dimensionality of the system.

Complex resistivity

When analyzing the response of materials to alternating electric fields, as is done in certain types of tomography, it is necessary to replace resistivity with a complex quantity called impeditivity (in analogy to electrical impedance). Impeditivity is the sum of a real component, the resistivity, and an imaginary component, the reactivity (in analogy to reactance) [1].

Resistivity density products

In some applications where the weight of an item is very important resistivity density products are more important than absolute low resistivity- it is often possible to make the conductor thicker to make up for a higher resistivity; and then a low resistivity density product material (or equivalently a high conductance to density ratio) is desirable. For example, for long distance overhead power lines— aluminium is frequently used rather than copper because it is lighter for the same conductance.

| Material | Resistivity [nΩ·m] | Density [g/cm³] | Resistivity-density product [nΩ·m·g/cm³] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium | 47.7 | 0.97 | 46 |

| Lithium | 92.8 | 0.53 | 49 |

| Calcium | 33.6 | 1.55 | 52 |

| Potassium | 72.0 | 0.89 | 64 |

| Aluminium | 26.50 | 2.70 | 72 |

| Copper | 16.78 | 8.96 | 150 |

| Silver | 15.87 | 10.49 | 166 |

Silver, although it is the least resistive metal known, has a high density and does poorly by this measure. The calcium and the alkali metals have the best products, but are rarely used for conductors due to their high reactivity with water and oxygen. Aluminium is far more stable.

See also

- Electric effective resistance

- Electrical conductivity

- Electrical resistance

- Electrical resistivities of the elements (data page)

- Electrical resistivity imaging

- Ohm's law

- Sheet resistance

- SI electromagnetism units

- Skin depth

- Superconductivity

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Serway, Raymond A. (1998). Principles of Physics (2nd ed ed.). Fort Worth, Texas; London: Saunders College Pub. p. 602. ISBN 0-03-020457-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Griffiths, David (1999) [1981]. "7. Electrodynamics". In Alison Reeves (ed.). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd edition ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 286. ISBN 0-13-805326-x. OCLC 40251748.

- ↑ http://physics.mipt.ru/S_III/t (PDF format; see page 2, table in the right lower corner)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Giancoli, Douglas C. (1995). Physics: Principles with Applications (4th ed ed.). London: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-102153-2.

(see also Table of Resistivity) - ↑ John O'Malley, Schaum's outline of theory and problems of basic circuit analysis, p.19, McGraw-Hill Professional, 1992 ISBN 0070478244

- ↑ Ni,Fe,Cr alloy commonly used in heating elements.

- ↑ Y. Pauleau, Péter B. Barna, P. B. Barna, Protective coatings and thin films: synthesis, characterization, and applications, p.215, Springer, 1997 ISBN 0792343808.

- ↑ Graphite is strongly anisotropic

- ↑ Hugh O. Pierson, Handbook of carbon, graphite, diamond, and fullerenes: properties, processing, and applications, p.61, William Andrew, 1993 ISBN 0815513399.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 The resistivity of semiconductors depends strongly on the presence of impurities in the material.

- ↑ Lawrence S. Pan, Don R. Kania, Diamond: electronic properties and applications, p.140, Springer, 1994 ISBN 0792395247.

Further reading

- Paul Tipler (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Electricity, Magnetism, Light, and Elementary Modern Physics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0810-8.